The Point of Being Blunt

On arcs, inflection points, and the record of presidents who say things plainly. As Biden has now done.

It has now been six days since Joe Biden gave his speech on “The Continued Battle for the Soul of the Nation,” at Independence Hall in Philadelphia. The official White House text is here; the C-Span video is here. I’ve looked at them both again today.

My purpose in looking back at the speech is to mention three point-in-time aspects of Biden’s performance in office that the speech helps illustrate.

—The first is the striking, systematic difference between immediate press and political reaction to what Biden says and does, and later responses. In brief: Biden usually gets panned in the short term for moves that look better later on.

—The second is about a divide in presidential rhetoric that applies to speeches like this one. In brief: presidents who have spoken this bluntly about national crises are usually (not always) later recognized and admired for it.

—The third is about how presidents invoke history in their speeches, and why I personally prefer to hear about “arcs” rather than “inflection points.”

1. The predictable cycle of Biden-reaction.

Response to most of what Joe Biden has done since taking office has followed a predictable reaction-curve:

—The first wave of response has been mainly skeptical, dismissive, critical, downcast about political effects. Biden unpopular; Dems in disarray. Examples below.

—Weeks or months later, many of those same “failures” and “missteps” have drifted out of regular news coverage, as their results have proven less catastrophic than foreseen, or as the administration has recalibrated and improved its policy, which is what administrations are supposed to do.

I am not talking here about criticism from the opposition, whether GOP officials or commentators on Fox. That’s two-party politics. I am talking mainly about the media’s role in creating a sense of ongoing governmental dysfunction, inability to cope, one more administration that has already failed even as it is getting underway. Much of this is through immediate reactions that either are raised-eyebrow cynical, or reduce everything to “what does this mean for the midterms?”

Here are some examples:

Three months ago, runaway inflation and “prices at the pump” led every print or broadcast news outlet. Political analysts explained why rising price-per-gallon had an outsized psychological and political effect.

Inflation is still a genuine economic worry, and the Fed’s response has had enormous effects. But gasoline prices have gone down every single day for nearly three months in a row. Somehow we’re no longer seeing photos of gas-station prices as background for news reports, nor hearing about those psychological and political effects.Almost every part of Biden’s legislative ambitions was pronounced “Dead, dead, dead” six months ago. Manchin; Sinema; McConnell; inflation; impending midterm disaster; Biden’s latest gaffe — if one of these obstacles didn’t stop the bills, the others would. Every TV analyst confirmed this. Now … things look different.

The midterm elections were called as a Republican landslide six months ago. The Democrats were dispirited and despairing. Now, who knows. (One iron law of media is: The Story Has To Change. Perhaps this principle is breaking in Biden’s favor just now.)

Biden’s comment soon after the Russian invasion of Ukraine that Vladimir Putin was “a war criminal” occasioned a week of press discussion about his verbal indiscipline and dangerous gaffes. But in the conduct of the war and support for Ukraine it had no lasting effect. (Similarly: Biden’s comments about Taiwan.)

Every year, under every U.S. president, we’ve seen stories about “crisis in the alliance,” within NATO or between the US and the EU. But those blocs are more aligned now (except for Brexit) than in decades. This has more to do with Vladimir Putin than with Joe Biden. But it has happened on Biden’s watch and with his supervision of U.S. policy. Perhaps I’ve missed them, but I haven’t seen many stories to that effect.

The baby-formula crisis; the container-ship crisis; the “wrong address for free Covid tests” crisis; the "economy feels bad" crisis; most other crises—all of these and others are still problems, but most are different from when they dominated the news. (A more complicated example is below.1)

The point of such a list is not that Biden is a “success” as president. We don’t know what’s ahead. He’s less than halfway into one term.

Rather it is that first-reaction, instant “take” press assessment has repeatedly erred in one direction. Try to think of a policy or decision for which Biden got better short-term coverage than he did after analysis had set in. I can’t think of any. On the contrary: most things Biden has tried or done look better, or less bad, a few weeks later than news coverage deemed possible at the time.

How is this connected to the Philadelphia speech? The first-wave coverage was overwhelmingly negative—about whether the tone was “political,” and about the presence of the Marines near the flags in the background, and about “calling out” Donald Trump by name.

After a while, reaction began shifting to what Biden actually said. Which brings us to …

2. The role of presidential bluntness.

Any student of rhetoric knows that presidents have at times been harshly direct, and at times benignly oblique, in talking about their political opponents.

On one extreme of bluntness, we have Franklin Roosevelt, just before his landslide re-election in 1936, in a famed address at Madison Square Garden. His best-known line from the speech was that “enemies of peace” were “unanimous in their hate for me — and I welcome their hatred.” He went on:

“I should like to have it said of my first Administration that in it the forces of selfishness and of lust for power met their match.

“I should like to have it said of my second Administration that in it these forces met their master.”

Seriously, this speech is an incredible stretch of rhetoric, well worth the time to hear or read. You won’t regret listening to it.

In 1963 John F. Kennedy was less blunt but nonetheless clear in a national address about sending troops to enforce desegregation orders in Alabama:

“Those who do nothing are inviting shame as well as violence. Those who act boldly are recognizing right as well as reality.”

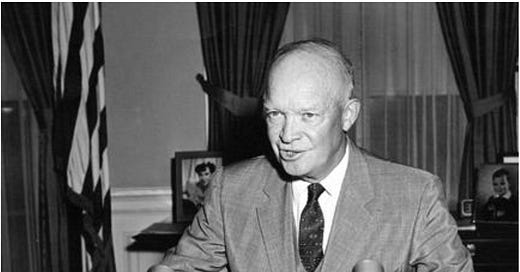

Six years earlier, in 1957, Dwight Eisenhower had been blunt in a national address about sending troops to enforce desegregation orders in Little Rock:

“In that city, under the leadership of demagogic extremists, disorderly mobs have deliberately prevented the carrying out of proper orders from a Federal Court…

“This morning the mob again gathered in front of the Central High School of Little Rock, obviously for the purpose of again preventing the carrying out of the Court’s order relating to the admission of Negro children to that school.”

Presidents differ, circumstances differ, styles of speech differ. But I contend that the long historical view has been more favorable to leaders who dared speak bluntly about what they viewed as threats to American democratic values, than to those who hesitated or hedged.

When Eisenhower hesitated.

Here is an example on the “hesitation” side: What was Dwight Eisenhower’s worst moment as a national leader? I contend that it came in his time as a candidate and early in his first term, when the demagogue senator Joseph McCarthy, Republican from Wisconsin, was on his destructive rampage.

As early as 1950, Margaret Chase Smith, a freshman Republican from Maine, had taken the Senate floor to give a speech known as the “Declaration of Conscience.” In it she warned that the Senate was being turned into “a forum of hate and character assassination.” In contemporary terms, you could think of Liz Cheney with her statements on the January 6 committee.

And you can think of the silent-or-worse response to Cheney’s warnings, from her fellow current GOP legislators, as resembling the response to Margaret Chase Smith from most of her fellow Republicans — including candidate and then president Dwight Eisenhower. More than four years later, in December, 1954, the entire Senate was finally ready to turn on Joe McCarthy, with a resolution of censure. But Eisenhower was notable in keeping his distance from Smith and her “conscience” caucus.

An excellent essay on the Miller Center’s “Age of Eisenhower” site explains that Eisenhower “despised” McCarthy privately—but kept those views mainly private until the end:

Looking at all the evidence, the clearest conclusion is that Eisenhower did not want to confront Joe McCarthy at all. And during 1953, he tried to avoid the whole issue, hoping the Senate would silence the explosive senator.

McCarthy was a Republican, after all, and many fellow senators supported him. Ike needed to keep his party unified to pass bills in other areas; battling McCarthy would only stir up a civil war inside the GOP.

Again draw your contemporary comparisons. And — if you are a Republican Senator or other aspirant — recall that this chapter of the great Dwight Eisenhower’s life is the one that reflects most poorly on him.

3. History as ‘arc,’ versus history as ‘inflection point.’

I’ll make this one quick. When a speaker wants to signal “I’m getting serious now,” two terms are readily at hand. One is “inflection point.” The other is “arc of the moral universe” (or sometimes “arc of history”), quoting Martin Luther King Jr., who was in turn quoting a 19th-century abolitionist and clergyman named Theodore Parker.

Joe Biden has long favored “inflection point,” and he used it in this latest speech: “I believe America is at an inflection point — one of those moments that determine the shape of everything that’s to come after.”

For myself—as a listener, as a writer, as a citizen—I’ve always preferred the arc idea. It reinforces the reality that history is re-determined every single day. (This is apart from whether that arc ultimately “bends toward justice,” which depends on your time horizon and which we’d like to believe is true.)

Although Biden didn’t use the term arc, the final five minutes of his speech were all about the history, the justice, the democracy, and the future that his fellow citizens are creating now. Or should be.

Tomorrow I’ll put up one of Substack’s “discussion threads” for elaboration by me, and by subscribers, on these and related points, as part of the expanded “backstage” policy I mentioned here. Thanks to all for reading, and for those who choose to join in for more.

The most complicated instance is Biden’s decision to withdraw from Afghanistan. I started making that part of the current post, and when it got too long I decided to save it for its own online discussion thread. For the moment I highly recommend the one-year-later collection of views about the withdrawal here.

For the record, as I’ve written in the past and will explain further, I think Biden made the right choice. I wish Obama had made the choice earlier. The point for now is: agree or disagree, it was a far more complex, carefully considered, and less immediately political decision than press coverage indicated.

All good points. It’s a pity Biden will likely pass before the country recognizes how good a man and prescient an administrator he actually is. But if that arc bends in the proper direction, the country will someday. And old Joe probably doesn’t give much of a damn anymore.

I just listened to that FDR speech. What a barnburner of a talk that was! I'm ready to vote for him now. It's instructive to look at how clearly he frames his issues. And you have to love the way he repeatedly hammers "Of course!" before affirming each goal of his administration.

What I found ironic and sad was the way various GOP figures and pundits attacked Biden's rhetoric as "divisive"--as if they had never heard a single one of Trump's speeches calling Dems "enemies" or "traitors" or "pedophiles," let alone the ferocious discourse every hour on Fox news.

The sight of these foul-mouthed defamers clutching their pearls is mighty rich.