The Court Can't Heal Itself.

‘Contempt of court’ takes on a whole new meaning. Clarence Thomas won't solve this problem, and John Roberts can't. It's time to bring rule of law to the law-deciders.

The post will highlight two long-ago Atlantic articles, not by me, that I have been thinking about recently. One is from Ronald Reagan’s era; the other, from George W. Bush’s. Together they dramatize the ethical collapse of today’s Supreme Court, and clarify why its current members won’t or can’t correct the situation.

The upshot of these pieces is that even law-deciders need to be brought under the rule of law. Which the Supreme Court, uniquely among political institutions, is not.

—Healthy societies depend on a combination of internal standards and external enforcement. You hope people will do the right thing on their own. But you have laws, penalties, speed cameras, et cetera just in case.

—Trust, but verify, as Ronald Reagan might have put it.

The Supreme Court has tried to get by on trust alone. “If we do it, then by definition it’s right.”

You can think of other long-revered institutions that coasted by, saying “Oh, just trust us,” and then burned up that trust. Name your religious denomination and you can think of the examples.

The larger life lesson is that everyone needs to know that someone else might be checking. It’s good that the aviation system has its NTSB reports. It’s good that the IRS is hiring more auditors. News organizations need more “public editors.” It would be good for the Supreme Court to have to follow rules.

Consider these two articles.

1) The longest-serving member of the Court: ‘I can’t pay no attention to Brad.’

Let’s start in early 1987. At the time Ronald Reagan was still in the White House. Clarence Thomas was only 38 years old. He was then the controversial head of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission but had no judicial experience or role.

It was about four years later that he received his lifetime position on the Supreme Court. Clarence Thomas will turn 75 this summer. He has been on the Court roughly half his adult life.

Back in those late Reagan days, Juan Williams was a rising-star writer for the Washington Post. I had known him in DC in the early 1980s and then in Japan in the late 1980s, when we both spent time there. Juan later became a figure on NPR, and then on Fox News.

His big piece for the Atlantic was a sweeping, ambitious profile of the young Clarence Thomas. You can read the whole thing here. I think it is worth another look, in history’s perspective.1

You’ll see that some of the references are strikingly dated. It was a long time ago. But most of what it discusses is amazingly relevant. And while reading it, recall that in early 1987 hardly anyone in the general public thought that Clarence Thomas would end up with life-or-death power over tens of millions of other Americans.

The premise of the article was not that Thomas would be world-changing but instead that he was interesting and “contrarian” in his views. Juan Williams, who is also Black, had been interviewing Thomas over a number of years.

This is the way Juan Williams’s article ends. I find it more powerful now than I did when I read it at the time:

In mid-September [1986], Attorney General Edwin Meese, Assistant Attorney General for Civil Rights Bradford Reynolds, and Senator Strom Thurmond, the former segregationist from South Carolina, came to the EEOC's offices to swear in Clarence Thomas. It was an unlikely sight—the three white men shaking hands and slapping backs with Thomas. Reynolds had days earlier attacked Supreme Court Associate Justice William Brennan as a man seeking "unlimited judicial power to further a personalized egalitarian vision of society" through racial preferences and a "liberal social agenda."

Meese was about to give a speech encouraging politicians to disregard Supreme Court rulings if they felt the rulings were wrong. Clarence Thomas, in his moment of triumph, stood shoulder-to-shoulder with his Administration colleagues. None of the three stayed more than a few minutes at Thomas's celebration. But before he left, Reynolds raised his glass. "It's a proud moment for me to stand here," he said, "because Clarence Thomas is the epitome of the right kind of affirmative action working the right way."

Clarence Thomas flinched. Some of his aides looked down and shook their heads. After all Thomas had been through in defense of the Administration position on civil rights, Reynolds had implicitly dismissed him as an affirmative-action hire. And, worse, Reynolds had thought it a compliment.

Thomas showed a look of cold hurt—a look of disgust. He folded his arms across his chest and looked away from Reynolds. By the time Meese had said a few words and Thurmond had sworn him in, an uneasy smile had returned to Thomas's face.

A few days later, when I asked about his reaction to Reynolds's comment, Thomas waved his hand, as if swatting away the memory. "I can't pay no attention to Brad," he said.

“I can’t pay no attention to Brad.” It might as well be the title for a book about Thomas’s time in public life.

—You don’t like what I’m doing? That’s your problem. I can’t pay attention.

—I don’t ask any questions during several decades of oral argument? Tough. I’m in this seat, and you are not.

—My wife is a highly paid activist for right-wing organizations, and a supporter of the January 6 insurrection even as I’m ruling on these cases? Again, what are you going to do about it? Show me the ethics rules we’re breaking. Oh, right—the Supreme Court doesn’t have any ethics rules.

—A right-wing billionaire becomes my “friend” and financial benefactor, having met me when I am already on the Supreme Court? What of it? Yeah, yeah: You might point out that wiser people who have risen to very high office realize that they can never make any “real” friends after they ascend to power. But Harlan Crow respects me for myself! He really likes me! That’s what he says, on the cruises and jet flights and sessions at the Bohemian Grove.2

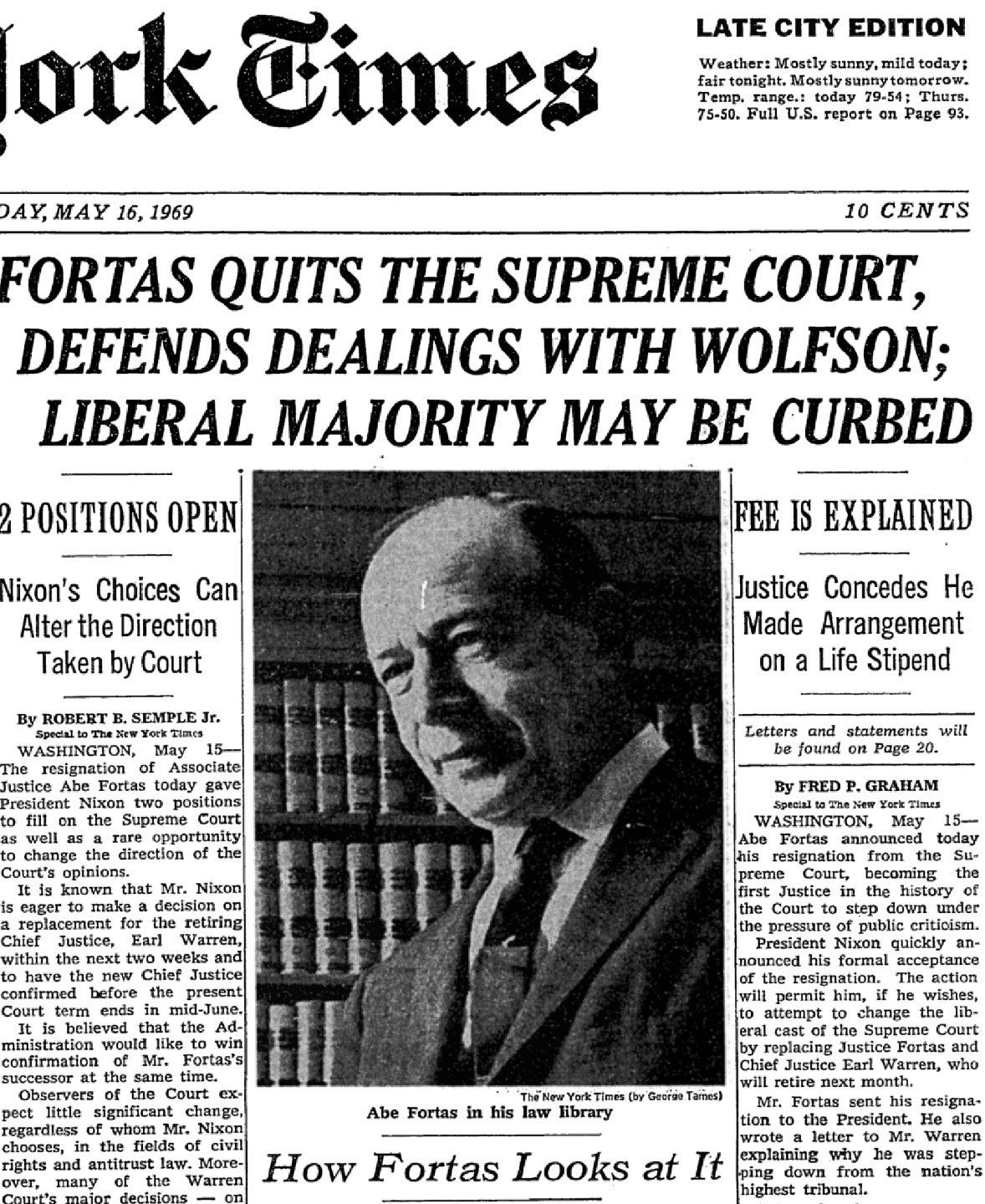

Does this look bad? It looks terrible. Back in the 1960s, Lyndon Johnson’s appointee Abe Fortas resigned from the Court, because of financial involvements that were penny-ante compared with those of Thomas, his wife, and his mother. No law “made” Fortas step down, although there were impeachment threats. But he felt he “had” to.

2) Supposedly the most powerful member of the Court: ‘Please don’t call us politicized.’

Who has paid attention to appearances? The Chief Justice since 2005, John G. Roberts. By all accounts, he cares tremendously about how he and his colleagues are seen, and how he will be remembered.

Let’s stipulate, as the lawyers say, that Roberts came to the Supreme Court with a partisan background. He is one of three members of the current court who were part of George W. Bush’s legal team in the 2000 Florida-recount struggle, leading to the infamous Bush-v-Gore ruling, which lastingly changed the gyre of 21st century America. (The other two are Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett.) And in 2013 Roberts himself was author of the also-infamous Shelby County ruling, which effectively undid the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

But I’m writing to direct your attention to an Atlantic cover story from 16 years ago, by Jeffrey Rosen, about what the then-shiny new Chief Justice Roberts hoped his legacy would be. After finishing his first term as Chief, Roberts reflected with Rosen about his eye toward history. For instance:

“It’s sobering to think of the seventeen chief justices; certainly a solid majority of them have to be characterized as failures,” Roberts said with a rueful smile. “The successful ones are hard to number.”

I asked him to elaborate: Why had so many chief justices been failures? Partly, Roberts explained, it was because the powers of the office are not extensive. “A chief justice’s authority is really quite limited, and the dynamic among all the justices is going to affect whether he can accomplish much or not,” he said.

“There is this convention of referring to the Taney Court, the Marshall Court, the Fuller Court, but a chief justice has the same vote that everyone else has.” As a result, “the chief’s ability to get the Court to do something is really quite restrained.”…

In Roberts’s view, the most successful chief justices help their colleagues speak with one voice. Unanimous, or nearly unanimous, decisions are hard to overturn and contribute to the stability of the law and the continuity of the Court; by contrast, closely divided, 5–4 decisions make it harder for the public to respect the Court as an impartial institution that transcends partisan politics.

Roberts suggested that the temperament of a chief justice can be as important as judicial philosophy in determining his success or failure. And based on the impression he made in his first year on the Court and throughout his career, Roberts seems to have many of the personal gifts and talents of the most successful and politically savvy chief justices.

That was then. Now, as Adam Liptak put it in the NYT, “In the most important case of his 17-year tenure, Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. found himself entirely alone.” This was the Alito-Thomas ruling in Dobbs, explicitly overturning Roe v. Wade.

Back then, Roberts told Rosen: “I think the Court is also ripe for a similar refocus on functioning as an institution, because if it doesn’t it’s going to lose its credibility and legitimacy as an institution.”

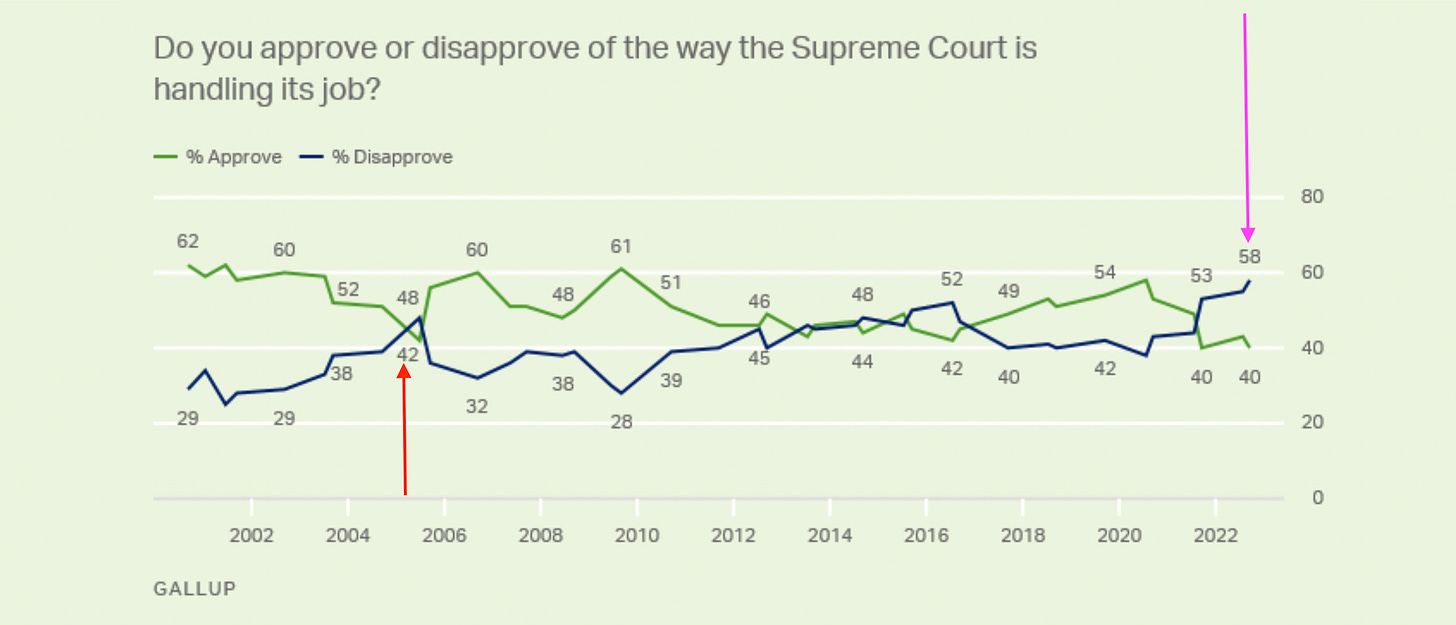

And now we have the Court losing its credibility and legitimacy as an institution. The Gallup chart below shows mistrust in the Court at a record level. (The dark blue line is disapproval.) The red arrow marks when Roberts came onto the Court. The purple one is its current level, after the Dobbs ruling. Fifty-eight per cent of those polled now “disapprove” of the Supreme Court’s performance.

In 2020, Rosen revisited the Roberts record and wrote an article called “John Roberts Is Just Who the Supreme Court Needed.” It said, “Roberts worked to ensure that the Supreme Court can be embraced by citizens of different perspectives as a neutral arbiter, guided by law rather than politics.”

Maybe. Maybe Roberts could defend the Court against the Thomas taint by doing something, publicly or privately. Maybe. But not likely.

Remember that in addition to Thomas, the “Roberts court” includes one member (Gorsuch) who is in place only because Mitch McConnell stonewalled a previous nomination; another (Kavanaugh) whose six-figure credit card debt somehow disappeared before his controversial confirmation; and a third (Barrett) whose appointment the same Mitch McConnell rammed through after just days before Donald Trump lost his re-election race.

3) What now?

Let’s try the process of “diagnosis by exclusion.”