The Political Press Needs a Time Out

It's tough to make predictions, especially about the future. How about if we waste less time trying: A proposal.

So much is still in flux from the 2022 midterms. The control of the House and the Senate could go either way. The political careers of Herschel Walker, Lauren Boebert, Kari Lake, Blake Masters, and others may be ending—like that of Mehmet Oz. Or they could just be getting underway, like that of J.D. Vance.

Joe Biden could have a much harder time ahead of him in appointing judges. Or easier. We don’t know.

Here’s what we do know:

First, that the results will not be remotely on a scale with previous first-term midterm wipeouts, especially for Democrats. As a reminder, among post-World War II Democratic presidents:

In 1946, Harry Truman’s Democrats lost 55 seats in the House, and 12 in the Senate, in his first election after succeeding FDR and ending World War II.

In 1962, John Kennedy lost 5 seats in the House, after his guidance through the Cuban Missile Crisis.

In 1966, Lyndon Johnson lost 47 seats in the House but still held a majority because of the Democrats’ landslide victories over Barry Goldwater in 1964.

In 1978, Jimmy Carter lost 15 seats.

In 1994, Bill Clinton lost 54 seats, and Newt Gingrich became the first Republican Speaker of the House since the 1950s.

In 2010, Barack Obama lost an astonishing 63 seats, the worst midterm defeat ever.1

Every first-term president since World War II (except one) has suffered midterm election losses. The average loss has been around 30 House seats. The one exception is George W. Bush in 2002, then at a height of public support after the 9/11 attacks and before the invasion of Iraq. His party gained 8 seats in the House.2

A lot has changed over this span—including, crucially, that far fewer House seats are potentially “in play” any more, since so many have been gerrymandered into one-party locks. But in historic terms, the midterm results under Joe Biden in 2022 are likely to be far better for the incumbent party and its president than for other modern presidents. As Biden would say, it’s a BFD.

Second, what has happened appears to be entirely at odds with what the political-reporter cadre — the people whose entire job is predicting and pre-explaining political trends — had been preparing the public for.

What the ‘pre-write’ looked like.

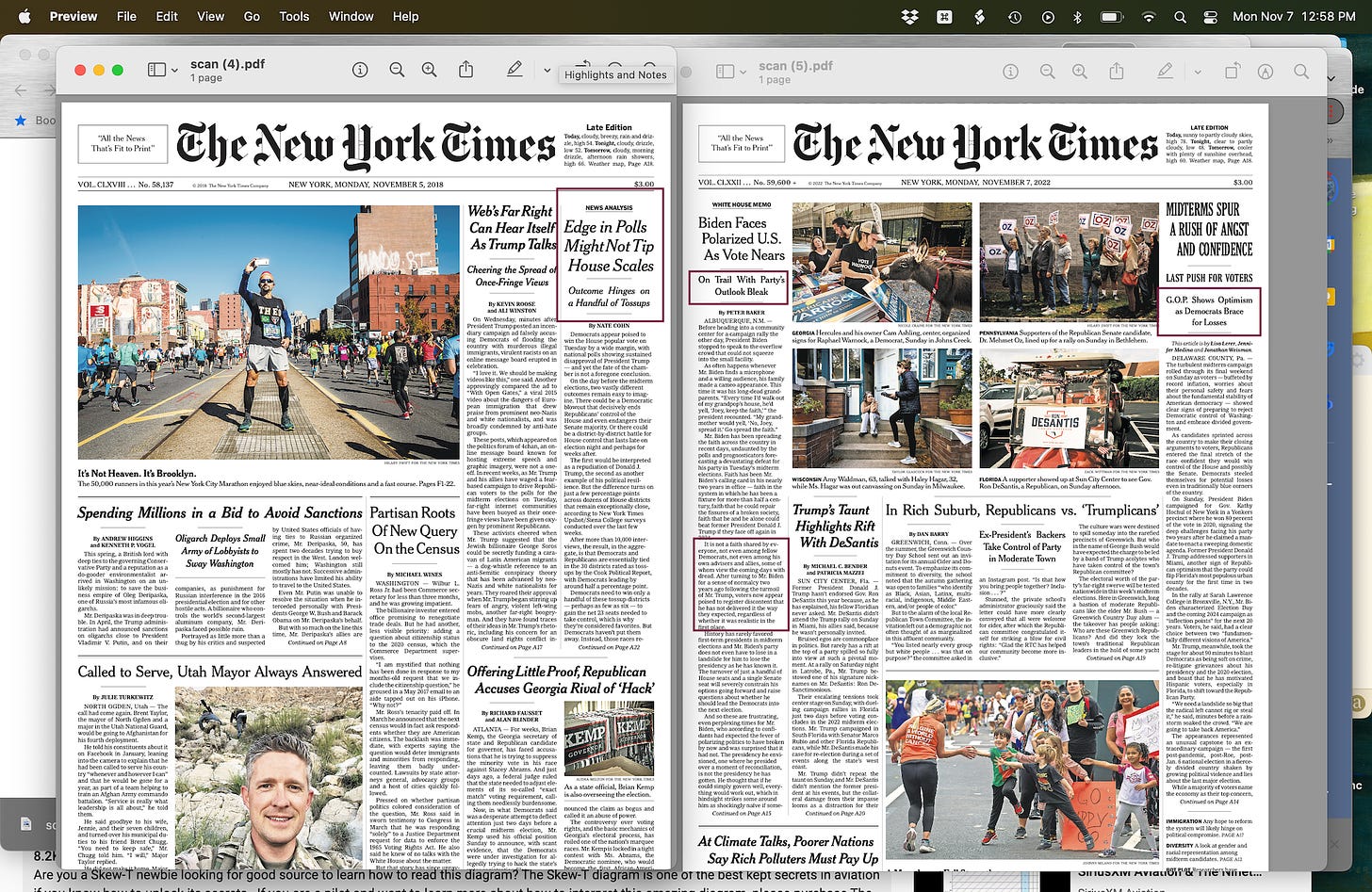

For an illustration of how prepared our leading press organizations were to declare a Biden failure and a Republican sweep, consider the early edition of the New York Times, which went to the printer last night as the first results, of GOP flips in gerrymandered Florida districts, were coming in:

What's perhaps most notable about this page is not just the declaration that the initial Florida results were "pivotal" or the context that the Democrats "face intense national headwinds." It is also the play of the “explainer” story on the left side, obviously planned in advance, with its premise that the U.S.'s self-correcting tendencies would have been shown once again to have failed.3

And here is a pre-write from the front page of this morning’s WSJ. The news operations of the Journal (as opposed to its Fox News-counterpart editorial pages) have overall been much more careful about a “Dems in disarray” framing of the 2022 election than the Times has.

But the framing the Journal was prepared for was “pocketbook issues” — inflation, interest rates, “pain at the pump”—determining results. This seems to be what some people who answered their exit polls claimed, but it doesn’t appear to have been what happened.

What did happen? The Washington Post gave a clue with an online banner this afternoon, making a point notably absent from most of the pre-writes:

The pre-narrative we have heard.

The Democrats have “defied expectations,” as the Post headline above puts it, largely because of the expectations our media and political professionals had set.

The premises of “analysis” pieces and talk shows over the past year-plus have been:

“Biden is unpopular,” which may be true but seems not to have been decisive.

“Afghanistan was the effective end of his presidency,” a widespread view 14 months ago. You can look it up.

“Democrats have no message” — which in turn is an amalgam of (a) “Roe was a long time ago,” (b) “no one cares about infrastructure,” (c) “it’s all about crime” [or immigrants], and (d) “it’s all about Prices At The Pump.” Here is a representative Page One framing from the NYT just one week ago, which I mention because of how much the NYT shapes and legitimizes other coverage:

“Dems in disarray.” On the day before people went to the polls, the Times’

front page had two “analysis” stories on how bleak the Democratic prospects looked. Below you’ll see a comparison of this week’s pre-election front page, on the right, with the one four years earlier, the day before the Trump midterms of 2018.

In 2018, shown on the left, the analysis stressed the uncertainty of how things would go. This is always the right note for election-week coverage to strike. And as it turned out, the Democrats had a huge win, gaining their 41 seats.But in 2022, two days ago, the front-page stories and framing were different. They said: “[Democratic] party’s outlook bleak,” “[Dems] view the coming days with dread,” “brace for losses,” “clear signs of rejecting Democratic control.”

It’s not so much that this proved to be wrong. It’s that they felt it necessary and useful to get into the "expectations" business this way.4

What is to be done.

Prediction is hard. But there are people who have to keep trying:

Weather forecasters give us advice on matters from the trivial (“Be sure to bring your umbrella!”) to the consequential (“You must evacuate now”).

Business analysts suggest trends for companies, technologies, entire economies.

Climate scientists give guidance on drought, floods, shifts in crops.

Epidemiologists tell us where new threats may arise.

None of them is perfect. But we depend on all of them giving us their best guess.

If any of them was as off-base, as consistently, as political “experts” are, we’d look for someone else to do those jobs.

Or ask whether it even needs doing. Which in politics it only rarely does. If you had never read an “expert” analytic column on “what this means for the midterms,” or gone to a single political-insider panel discussion, you’d be about as well informed on what has just happened as if you’d spent all day every day doom scrolling.

There is so much to explore, learn about, and share in our world. Speculating on what’s going to happen in the next election is about the least useful insight to add.

I thought of this when I saw the first stories about “why Biden faces trouble in the midterms” stories 18 months ago. I will think about it tomorrow when I read the next “How this shapes the 2024 field” speculation-fest.

No one knows what is going to happen. Least of all — it seems — the political “experts.” So let’s waste less time pretending to know, and invest more in looking into, sharing, and learning from what is actually going on.

How about this, in practical terms: For the next three stories an editor plans to assign on “Sizing up the 2024 field,” or the next three podcasts or panel sessions on “After the midterms, what’s ahead for [Biden, Trump, DeSantis, etc.],” instead give two of those reporting and discussion slots to under-reported realities of the world we live in now.

Whatever you say about the 2024 race now will be wrong. And what you say about the world of 2022 could be valuable.

It’s hard to make comparisons to midterms before the early 1900s, because the House itself used to be much smaller. The very first Congress had only 59 House members. Census by Census the number went up, to 435 after 1910. It has been frozen there ever since, even though the U.S. population is about three-and-a-half times larger. For a trenchant argument on why the House needs to expand, see this passage from Our Common Purpose, from the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

And among first-term Republicans: in 1970, Richard Nixon’s GOP lost 12 seats; in 1974, Gerald Ford lost 49 seats (after Watergate and Nixon’s resignation); in 1982, Ronald Reagan lost 26; in 1990 George H.W. Bush lost 7; and in 2018 Donald Trump lost 41.

It’s by the wonderful Damien Cave, at one point a student in the course I taught with Katie Hafner at the UC Berkeley Journalism School. I am talking about the spring-loaded play of the story, not what the story says.

I will say it one more time. In the overall scope of its coverage, the NYT is an extraordinarily ambitious, creative, imaginative, responsible, and standard-setting news organization. Science; arts; books; technology; climate; health; graphics; national security; global issues; photography; the magazine; the “kids edition”; drama; a new approach to sports; puzzles … on down the list.

Then there is its approach to domestic U.S. politics.

One clear route to more democratic elections was demonstrated in my home state of Michigan, where 2020 redistricting was done by a bipartisan commission. The result: our congressional delegation now comprises 7 Democrats and 6 Republicans, nearly identical to the distribution of partisan registration. And both houses of our state legislature have flipped from Republican to Democratic majorities. Here's an excellent roadmap for states that can change election rules by ballot propositions: establish nonpartisan redistricting commissions and let the people vote...

"There is so much to explore, learn about, and share in our world. Speculating about what’s going to happen in the next election is about the least useful insight to add." Amen. One of the hidden costs of all this fruitless speculation is that it takes time, talent and attention away from real reporting.